從地名考察台北市歷史

從地名考察台北市歷史

Using place names to look at Taipei’s history

戴寶村/Tai Pao-Tsun

(中央大學歷史系教授)

(Professor, History Department, National Central University)

2001-09-17

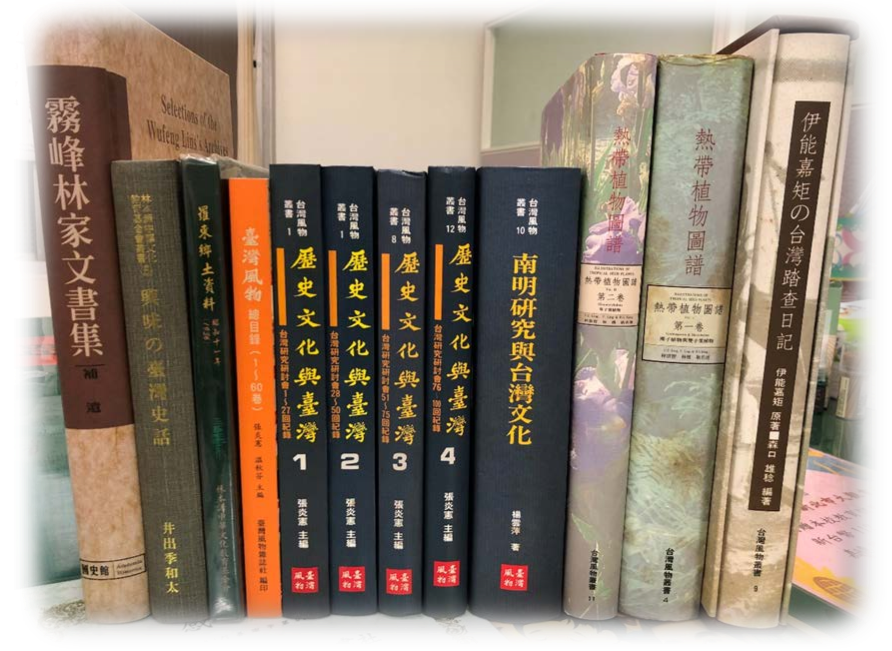

“Manka” is a word meaning “canoe” in one of the Pingpu languages.

This picture shows a covered arcade in a street in Manka in the 1931.

台北市是台灣最大的都市,也是國際著名都市,快速的都市化改變了台北的舊貌,但從一些地名可以看出台北的歷史發展軌跡,真的是「一步一腳印,處處皆歷史」。

Taipei is Taiwan’s largest city, and an internationally famous one. Its rapid transformation into a metropolis changed the old face of Taipei, but inspection of some of its place names can show us the developing trajectory of Taipei’s history. It’s really true that for each step we take, we uncover a piece of history.

平埔族與西、荷殖民者的詮釋方式

台北盆地原先是一般通稱凱達格蘭平埔族原住民居住、生活之地,平埔族和漢人長期接觸後已喪失其族群與文化特質,但仍留下一些常見的地名,如「大屯山」源自平埔族的社名,荷蘭時代寫作Touckenan,「北投」原來拼音字為Kipatauw是「女巫」的意思,士林地區舊名「八芝蘭」意思是溫泉,松山舊名錫口,內湖地區的「塔悠」荷語拼音為Cattajo,是指婦女的頭飾,「大龍峒」原名「大浪泵」和「秀朗」都是平埔族的社名,「艋舺」是指獨木舟,「社子」是漢人指稱平埔族的部落所在。

Explanatory notes on the Pingpu tribes and Spanish and Dutch colonists

The Taipei basin was once generally known as the home of the Ketagalan people, one of the Pingpu tribes. After a long period of contact between the Pingpu and Han peoples, the Pingpu people lost external signs of their ethnicity and culture, but they did retain some commonly-seen place names, such as “Tatun Mountain,” a name which derives from a Pingpu placename, and which was written as “Touckenan” in the Dutch era. “Peitou” was originally spelt “Kipatauw,” meaning “witch,” and the old name for the Shihlin district was “Pattsiran,” which meant “hot springs.” The old name for Sungshan was “Tsigauantsigau.” The Neihu district was known as “Tayou,” or, as the Dutch wrote it, “Cattajo,” indicatinga woman’s head ornament. Talungtong was originally called “Pourompon” and “Sirongh,” both of which are names of Pingpusocieties. “Manka” means “canoe” , “Shetzu” was the Han people’s name for a place where the Pingpu peoples lived.

西班牙人在1571年東來取得菲律賓作為殖民地,1626年佔領北台灣,據說東北角的「三貂角」與San Diago有關,1628年在淡水河口山丘建聖多明哥(St. Domingo)城,附近的「關渡」一般台語稱「甘豆」,有一說是來自西班牙文Casidor(岬角)的意思。淡水捷運線有一站名「唭哩岸」,荷語拼音為Kirananna,起源自西班牙人將菲律賓群島的一海灣Bahia-Irigan的名稱移用而來。

In 1571, The Spanish came east and took the Philippines as a colony. In 1626, they captured Taiwan, and it is said that San Tiao Chiao, the name of the northeast tip of Taiwan, comes from the name the Spanish gave this place, San Diago. In 1628, the Spanish built the fort of San Domingo in the hills at the mouth of the Tamshui River, and Kuandu, called “Gamdau” (lit. “sweet bean”) in Taiwanese, is, according to one version, taken from the Spanish “casidor” (meaning “cape”). There is a station on the Tamshui MRT line called “Chili An”, a place name which was spelt “Kirananna” by the Dutch. Thename’s origins derive from a bay in the Philippines which the Spanish called “Bahia-Irigan.”

清代墾荒者的足跡

1683年清帝國領有台灣後,福建、廣東地區漢人大量渡海來台,1709年「陳賴章」墾號(開墾組織)開拓台北盆地,村莊陸續形成,於是有「新莊」、「舊莊」(在南港)的聚落名稱,如果是同姓聚居之地,便有「朱厝崙」(長安東路附近)的地名。盆地周邊具有地形特徵的山丘出現如「圓山」、「蟾蜍山」、「觀音山」、「五指山」、「七星山」等的地名,地形比較平坦的地區稱作「埔」,如「內埔」、「五分埔」,有突起之地稱為「中崙」,溪流則有「雙溪」、「磺溪」、「新店溪」等。表示聚落位置的地名有「南港」、「內湖」、「溪口」、「林口」、「坪頂」等。而在開拓初期有些動植物也會用作地名如「山豬窟」、「鹿窟」,是指有低漥水池山豬和鹿常出沒之地,台灣過去樟樹甚多,南港附近有「樟樹灣」的地名。

Footprints left by pioneers from the Qing Dynasty

In 1683, after the Qing empire took Taiwan, Han people from Fujian and Guangdong began to cross the sea to Taiwan in large numbers. In 1709, the Chen Lai-chang Development Company opened up and developed the Taipei Basin, and villages grew up one after another, so we have the names “Hsin Chuang” (“new village”) and “Chiu Chuang” (“old village,” this is a place name in Nankang) as names of settlements. If these places were communities where inhabitants shared a common family name, then we have the place name “Chu Tsuo Lun” (near to Chang An East Road). Around the Taipei Basin are hills and mountains with topographical characteristics such as “Yuanshan” (“round mountain”), “Chanchu Shan” (“toad mountain”), “Kuanyin Shan” (“Goddess of Mercy mountain”), “Wuchih Shan” (“five fingers mountain”) and “Chi Hsing Shan” (“seven stars mountain”). In areas where the topography is flatter, we see “pu” (“plain”) appearing in place names, such as “Neipu” (“inner plain”) and “Wufenpu.” Where the land rises up, we have “Chung Lun” (“center mountain”). Where streams and rivers flow, we have “Shuanghsi” (“twin streams”), “Huanghsi” (“sulphur stream”), “Hsintienhsi” (“Hsintien stream”), etc. Names which show the position of settlements include “Nankang” (“south harbor”), “Neihu” (“inner lake”), “Linkou” (“entrance to the woods”) and “Pingting” (“top of the level ground”). Back when land development was beginning, certain animals and plants were also used in place names, such as “Shanchu Ku” (“mountain boar’s den”) and “Lu Ku” (“deer’s den”). These names indicate low-lying lakes haunted by mountain boar and deer. In the past, Taiwan had many camphor trees, and in there is a place near to Nankang called “Changshu Wan” (“camphor tree bay”).

漢人在拓墾台北時留下很多與農業相關的地名,如數人合作開墾便有「五股」、「十八份」(在北投)的地名,水田稻作需要建設水利灌溉設施,因此有「(王留)公圳」、「永春埤」、「大安埤」。土地開墾後要計算面積,沿用荷蘭時代的「甲」(acre),過去一隻耕牛能耕作的面積約五甲地,所以有「三張犁」、「六張犁」、「七張犁」、「十二張犁」的名稱,要曬乾收成稻穀的地點叫「大稻埕」,有設商店營業之地稱「新店」,地主收租辦公之處叫「公館」。

Han people have left behind them many place names connected with agriculture from the days when they were developing Taipei. For instance, a number of people cooperated to develop the land, and left the names “Wuku” (“five shares”) and “Shipafen” (“eighteen portions,” a place in Peitou). Paddy fields necessitated the construction of irrigation systems, and so we have the names “Liukungchun” (“Liu public irrigation ditch), “Yungchunpei” (“eternal spring irrigation ditch”) and “TaAnPei” (“great peace irrigation ditch”). After the land was developed, people had to calculate the area of the land, and they continued to use the “jia” (roughly, acre) from the Dutch era as a unit of measurement. In the past, the area of land an ox could plow was around five jia, and so we have the place names “Sanchang Li” (“three areas to plow”), “Liuchang Li” (“six areas to plow”), “Chichang Li” (“seven areas to plow”) and “Shiherhchang Li” (“twelve areas to plow”). The place where harvested rice was put out to dry was called “Tataocheng” (“big plaza for rice”), and the place designed for shops and firms to run their businesses was called “Hsintien” (“new shop”). The place where landlords collected rent and had their offices was called “Kungkuan” (“villas” owned by these rich landlords, where they would collect the rent).

漢人開拓過程中會與原住民發生衝突,因此設置防禦措施以保安全,栽種竹子成為圍籬以防外人侵入就是「竹圍」,若用木材構築成柵欄則稱「木柵」,若構築土牆就稱「土城」,新店溪流域還有「頂城」、「二城」帶有順序意義的地名。清帝國政府鑑於漢人與原住民常滋生衝突,於是在分界處設置石碑,約束漢人不得越界侵墾,妨礙平埔族生計,「石牌」現尚存在,並移置於捷運站展示,作為歷史的見證。

In the process of developing and exploiting the land, clashes occurred between Han people and Aboriginal people, and so bamboo hedges were planted as defense measures to keep those inside safe and prevent outsiders from invading. One such place was called “Chuwei” (“bamboo surroundings”). If wood was used to build fencing, then it was called “Mucha” (“wooden fence”), if earthen ramparts served the same purpose they were called “Tucheng” (“earthen city wall”). In the Hsintien Creek basin, there still exist place names that show the order of these fortifications: “Tingcheng” (“top city wall”) and “Erhcheng” (“second city wall”). In view of the frequent clashes between Han and Aboriginal peoples, the Qing government installed stone markers on the boundaries, restraining the Han people from developing any land beyond the boundaries, which might jeopardize the Pingpu people’s livelihoods. The original “Shihpai” (“stone marker”) still exists, and has been put on display at Shihpai MRT station, where it stands as a witness to history.

Taipei’s development as a metropolis started in the three city areas of Manka,

Tataocheng and Chengnei, and gradually extended eastwards to make up the city we see today.

This picture shows Tataocheng’s Chienchiu Street in 1958 (today South Kueiteh Street).

1882年至1884年台北建城,今忠孝西路、中華路、愛國西路、中山南路所圈起的範圍就是所謂的「城內」,承恩門外之地就是「北門口」,台北市的都市發展就是以艋舺、大稻埕、城內三個市街中心逐漸連接再向東延伸擴大形成今日之風貌。

The city of Taipei was established between 1882 to 1884, and the area bordered by today’s Chunghsiao West Road, Chunghua Road, Aikuo West Road, Chungshan South road was what was known as the “Chengnei” (“inner city”). The land outside the Cheng’en Gate is the “Peimenkou” (“north entrance”). Taipei’s development as a big city started from the three city areas of Manka, Tataocheng and Chengnei, and gradually extended eastwards to make up the city we see today.

Many modern, public buildings were constructed during the Japanese colonial period,

Many modern, public buildings were constructed during the Japanese colonial period,

establishing the foundations of Taipei as a modern city.Union Hall (today’s Chungshan Hall)

Taihoku Prefecture Hall (today’s Control Yuan)

Taihoku Prefecture Hall (today’s Control Yuan)

日本殖民時代的遺痕

1895年日本領有台灣之後,台北延續先前清代省城的地位,成為殖民統治的行政中心,日本人拆除城牆,建設甚多現代公共建築,如總督府、法院、總督官邸、專賣局、公會堂、銀行、車站、新公園、博物館、醫院、學校等,奠定台北現代都市基礎。日本人在1920年代更改很多台灣的地名,台北地區如將「水返腳」改為「汐止」,「錫口」改為「松山」,「艋舺」改為「萬華」等,也有日式的街區名,如「樺山町」(紀念首任總督)、「馬場町」、「日新町」,其中的「西門町」一直沿用至今。

Vestiges of the Japanese colonial era

After Japan took possession of Taiwan in 1895, Taipei continued to be the provincial capital it had been under the Qing, and became the administrative center of colonial rule. The Japanese tore down the city walls, and build a great many contemporary public buildings, such as the Governor’s Office (Japanese:Sotofuku), law courts, the official residence of the Taiwan Governor, the Monopoly Bureau, Union Hall (today’s Chungshan Hall), banks, railway stations, new parks, museums, hospitals, schools and more, establishing the foundations for Taipei as a modern city. In the 1920s, the Japanese changed many of Taiwan’s place names. Places in the Taipei region such as Shuifanjiao, which became “Shiosi,” the Japanese pronunciation of today’s Hsichih. Hsikou became “Matsuyama” (Mandarin pronunciation:Sungshan), Manka became “Banka” (Mandarin pronunciation:Wanhua), etc. Urban street blocks were also named in the Japanese style, giving us “Kabayama Machi” (“Huashanting”, commemorating the first Japanese governor of Taiwan, Motonori Kabayama), “Umaba Machi” (“Machangting”), “Nishin Machi” (“Jihshinting”), and one which we still have today, “Seimon Machi” (Hsimenting).

中華民國政府的政治教條意味遍及大街小巷

1945年中華民國政府接收台灣之後,先廢除帶有日本色彩的地名,1949年中央政府遷台後,大肆更改或新命台灣的地名、街路名,台北市尤其顯著,這些街路名有以下原則,一、中國省市名稱:台北市化成中國大陸的縮影,如迪化街、哈密街、蘭州街、庫倫街、成都路、西寧南北路、長沙街、西藏路、康定路、桂林路、汀州路、廈門街、福州街、溫州街、鎮江街、北平路、天津街、南京東西路、龍江街、撫遠街,這些都是表示懷念固有國土之意;二、表現光復國土之意:如光復南北路、復興南北路、建國南北路、成功路等;三、傳播政治理念:如辛亥路、莒光路、三民路、民族、民權、民生東西路、莊敬路、自強路、愛國東西路等;四、倫理道德價值觀:如四維路、八德路、忠孝東西路、仁愛路、信義路、和平東西路、敦化南北路、安和路、樂利路、康寧路、忠誠路、德行東西路、行義路、知行路、仰德路、實踐街等;五、政治人物的街路名:如延平南北路、中正路、中山南北路、逸仙路、林森路、雨農路、羅斯福路等;以上這些地名純粹是政治意識下的產物,與歷史發展過程中自然生成演變的地名相去甚遠,難以讓民眾對該地名、街路名產生親近的互動關係,只有作為地址識別用途而已。

The R.O.C. government’s political doctrines cover big streets and little alleys

After the Nationalist Government took over Taiwan in 1945, the first thing they did was to get rid of place names which were too Japanese. In 1949, after the central government moved to Taiwan, it vigorously changed or reordered Taiwan’s place names and street names, particularly in Taipei, along the following principles: 1. Names of Chinese provinces or cities. Taipei City became mainland China in miniature, hence Tihua Street, Hami Street, Lanchou Street, Kulung Street, Chengtu Road, Hsinning Road, Changsha Street, Hsitsang (Tibet) Road, Kangting Road, Kuilin Road, Tingchow Road, Hsiamen Street, Fuchou Street, Wenchow Street, Chenchiang Street, Peiping (Beijing) Road, Tientsin Road, Nanking East and West Roads, Lungchiang Street, Fuyuen Street:all these display a longing for China. 2. Names which have the meaning of a country restored to its owner: Kuangfu North and South Roads (lit. “retrocession”), Fuhsing North and South Roads (lit. “renaissance”, “rebirth”), Chienkuo North and South Roads (lit. “build the country”), Chengkung Road (lit. “success”), etc. 3. Names broadcasting political ideas, such as Hsinhai Road (“Hsinhai” is 1911 in the lunar calendar, the year of Sun Yat-sen’s revolution overthrowing the Qing), Chukuang Road (Chu was a state in ancient China, “chukuang” means the light, or glory, of Chu), Sanmin Road (Sun Yat-sen’s “three [principles of the] people”), namely Mintsu, Minchuan and Minsheng (nationalism, democracy and livelihood). Also Chuangching Road (“dignity”), Tzuchiang Road (“self-strengthening”) and Aikuo East and West Roads (“love the country”). 4. Ethical and moral values: Siwei Road (“four virtues”), Pateh Road (“eight virtues”), Chunghsiao East and West Roads (“loyalty and filial piety”), Jenai Road (“benevolent love”), Hsinyi Road (“trust and appropriate behavior”), Hoping East and West Roads (“peace”), Tunhua North and South Roads (“education through acculturation”), Anho Road (“peace”), Loli Road (“enjoy gain” -gain for the country, not the individual, of course), Kangning Road (“health and tranquillity”), Chungcheng Road (“loyalty”), Tehsing East and West Roads (“virtuous conduct”), Hsingyi Road (“appropriate conduct”), Chihsing Road (“knowledge [is hard but] action [ is easy]”), Yangteh Road (“pursue virtue”) and Shichien Road (“praxis”). 5. Roads and streets named after political figures, such as Yenping North and South Roads (Yenping is one of Koxinga’s names), Chungcheng Road (for Chiang Kai-shek, one of whose names is Chiang Chung-cheng), Chungshan North and South Roads (for Sun Yat-sen, one of whose names is Sun Chung-shan) and Yi-hsien Road (the Mandarin pronunciation of “Yat-sen”), Linsen Road (for Lin Sen, president of China, 1932-43), Yunung Road (for General Tai Yu-nung, former head of the secret police), Roosevelt Road (for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt), etc. These place names are the outcome of a purely political consciousness, far removed from those names which came about as a natural result of the historical development process, and it’s hard for the public to feel a close relationship with these names. They are used purely for the purpose of identifying an address.

瞭解一個都市的歷史可以從歷史的遺址、史蹟、建築物、圖像、文字紀錄、口傳的故事或傳說等各種媒介途徑,而從自己居住的場所、工作、求學、休閒的地方的地名也可了解當地的部分歷史,舉足行止之地都有歷史,歷史的趣味與知識自然會累積為個人的人文涵養。

We can look to historical remains, footprints, buildings, maps, written records, orally transmitted stories and legends to understand a city’s history, and from the names of the places we go to meet, work, study and enjoy ourselves, we can also learn about local history. All places of action have a history, and an interest in and knowledge of history naturally build up a person’s humanity and tolerance.

Edited by Tina Lee/ translated by Elizabeth Hoile

李美儀編輯/何麗薩翻譯