農曆七月普渡與台灣社會

農曆七月普渡與台灣社會

Ghost Month and the Pudu rite

溫振華/Wen Chen-hua

(台灣師大歷史系教授)

(Professor, Department of History, National Taiwan Normal University)

2001-08-27

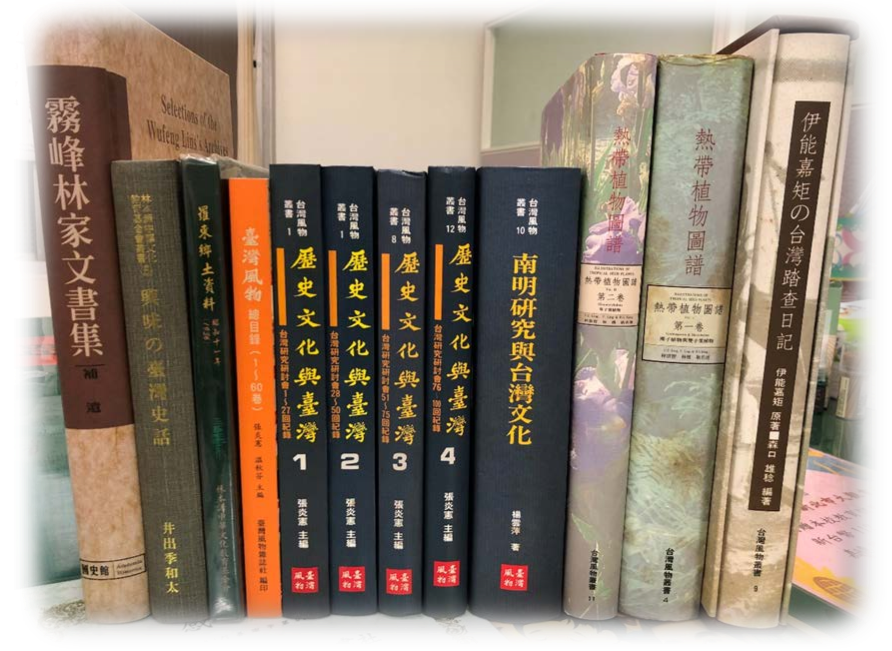

A man closes his eyes in prayer while holding a basket of fruits on the first day of Ghost Month in Lung Shan Temple in Taipei yesterday. According to legends, the gates of Hell are opened at the break of dawn on the first day of the seventh moon, letting the anguished souls in a world of darkness return to earth to visit their descendants and enjoy the feasts prepared in their honor.

A man closes his eyes in prayer while holding a basket of fruits on the first day of Ghost Month in Lung Shan Temple in Taipei yesterday. According to legends, the gates of Hell are opened at the break of dawn on the first day of the seventh moon, letting the anguished souls in a world of darkness return to earth to visit their descendants and enjoy the feasts prepared in their honor.

在早期的台灣社會中,孤魂野鬼被視為社會不安的源頭。因此,為安撫無人祭祀的鬼魂,於每年農曆七月舉辦融合佛、道兩教的普渡儀式。然而長達一個月的祭典儀式,不僅代表早期社會對鬼神的敬畏,也傳達了台灣人民對客死異鄉的孤鬼一種蘊含宗教情懷與同胞手足般的憐憫之情;十九世紀以後,普渡祭典的舉行更成為台灣社會區域人際網路連結的重要媒介。本週「台灣歷史之窗」特別邀請師大歷史系教授溫振華執筆,介紹此一融合幽暗與熱鬧的傳統節慶,並述說其在台灣社會中所獨具之特殊意義。

In early Taiwanese society, wandering ghosts were seen as the source of social disturbances, and so in order to placate these souls who had no one to carry out ceremonies for them, each year in the seventh month of the lunar calendar, the “Pudu” rite, which blends Buddhist and Taoist beliefs, was held. However, the month-long ceremonies and rites not only represent the fear and reverence that early Taiwanese society had for ghosts and gods, they also convey the religious and brotherly pity which Taiwanese people felt for the souls of those who had died in a strange land; after the nineteenth century, the holding of the Pudu rite became an even more important medium through which Taiwanese regional society could connect interpersonal networks. This week’s Window on Taiwan is written by Professor Wen Chen-hua of the history department at National Taiwan Normal University, who introduces this traditional festival which blends darkness and liveliness, and describes its unique and special significance in Taiwanese society.

鬼魂在漢人信仰中的意義

農曆七月為漢人俗稱的鬼月,月中的普渡是漢人社會一年中重要的祭典,祭拜無人奉祀的孤魂野鬼。要瞭解鬼魂在漢人信仰中的意義,可由下圖漢人的神鬼信仰體系來說明:

The Jade Emperor 玉皇大帝

Kuanyin, Matsu 觀音、媽祖

Paosheng, Chingshui 保生大帝、清水祖師

The Sage King Kaichang, the King of the Three Mountains 開漳聖王、三山國王

The God of the Earth 土地公

One’s ancestors 祖先

Wandering souls (also called the “answering men,” “the hordes of old men,” “the justice men,” “the Lao Ta men”, “the good men,” “the good brothers,” etc.)

孤魂野鬼(或稱有應公、大眾爺、義民爺、老大公、萬善爺、好兄弟……)

The significance of ghosts in Han belief

The seventh month of the lunar calendar is commonly called Ghost Month by Han Chinese people, and the “Pudu” rite in the middle of this month is an important sacrificial ceremony in Han society, when we offer sacrifices to those roaming dead souls who cannot be reincarnated, and who have no one to offer sacrifice to them. The diagram below explains Han people’s gods and spirits belief system, and may help you to understand the significance of Ghost Month in Han belief.

神界中,最高的神祇是玉皇大帝,其次是觀音、媽祖等等,最低的是土地公。鬼界中,有人供奉的是祖先,無人奉祀的是孤魂野鬼。孤魂野鬼由於無人祭祀,成為漢人信仰中,社會不安的重要來源。

The highest deity in the celestial world is the Jade Emperor, and after him come deities such as Kuanyin and Matsu. At the bottom of the pile is the God of the Earth. People sacrifice to their ancestors, and the wandering souls are those who have no descendants to sacrifice to them. Because wandering souls have no one to offer them sacrifice, they are a major source of social unrest in Han belief.

融合道教與佛教信仰的普渡儀式

面對社會不安之源的孤魂野鬼,發展出七月普渡的儀式,以安頓這些地獄中無人祭祀的惡鬼。今日農曆七月普渡,除了漢人的鬼魂信仰,也融入道教與佛教的思想,因此七月普渡常稱為「中元普渡」或「盂蘭盆會」。「中元普渡」之稱與道教思想有關,在道教的神祇中,有天官、地官、水官,地官執掌赦罪,於農曆七月十五日(即中元日)神祇生日降臨人間,定人之善惡罪福。孤魂野鬼被認為罪過較深,乃延請道士做科儀救渡眾孤鬼。「盂蘭盆會」是梵語之漢譯,意為施食拯救苦難。「盂蘭盆會」係釋迦牟尼告知其弟子目連於七月十五日以盆盛五果百味,供養十方大德,以救母脫離餓鬼道。由於佛、道兩教思想之滲入,中元普渡也有佛、道兩教不同的儀式。

The Pudu rite blends Taoist and Buddhist belief

The Pudu rite, or “Universal Salvation,” held in the seventh month, was developed to deal with the wandering souls, cause of so many problems in society, to help settle these demons in hell who have no one to sacrifice to them. These days, the Pudu rite blends not just Han beliefs about spirits and dead souls, but also Taoist and Buddhist thought, and so it’s often called the “Chungyuan Pudu” or the “Ullambana Rite.” The name “Chungyuan Pudu” is related to Taoist thought. In the Taoist pantheon, there are the Three Officials, of the sky, the earth and the waters. The Earth Official is in charge of absolution, and on the 15th day of the seventh month in the lunar calendar (the day known as Chungyuan), which is his birthday, he comes down to be among mortals, and decides who is good and who is bad, who will have suffering and who will have good fortune. The wandering souls were thought to have committed greater sins, and so Taoist priests are sent for to perform the “Ke Yi,” a discipline rite, and thereby rescue these lonely souls. “Ullambana” is a Sanskrit word which means to offer food to the souls of the dead and rescue them from their suffering, and is what the Buddha told his disciple, Mahamaudgalyayana. He told him that on the 15th day of the seventh month, he should go with basins full of “hundreds of flavors and the five fruits,” and offer them to the greatly virtuous assembled Sangha of the ten directions, and thus save his mother from the way of the hungry ghosts. Thanks to the mixing of Buddhism and Taoist thought, Chungyuan Pudu has two different Buddhist and Taoist rites.

普渡之儀式主要分成:請鬼、施食、誦經、驅鬼等。請鬼,是打開鬼門,迎請陰間的孤魂野鬼來到陽間。為讓眾鬼順利得由幽暗的地獄來到人間,人們在廟前豎立燈篙,上掛燈籠,上書「慶讚中元」,引導鬼魂。燈篙愈高,照明範圍愈大,來食的孤鬼就越多,因此各廟必須衡量自己能供食的程度,以免「鬼多粥少」,造成鬼魂的怨懟而加禍於人間。除陸上豎燈篙外,水中也有放水燈之儀式,照明來自水中的溺鬼。因深恐來到陽間的眾鬼不能滿足口食之慾,慎重的街市如鹿港,從鬼門開後,街民分組輪流按日供食祭祀,以保平安。

The Pudu rite can be split up into the following parts: inviting the ghosts, offering them food, reciting sutras, then driving the ghosts away again. Inviting the ghosts involves opening the ghost gate, and inviting the wandering souls to come up from the underworld into the light. So that the horde of ghosts can have a smooth passage from the gloomy underworld up into the world of mortals, people erect lantern poles in front of temples and hang lanterns, “celebrate Chungyuan” as mentioned above, and guide the ghosts. The higher the lantern poles, the larger the area they light up, and so the more lonely ghosts that can be fed. For this reason, each temple must consider the amount of feeding they can provide, so as to avoid having “too many ghosts and too little gruel” and angering the ghosts into bringing misfortune on humans. Apart from the lantern poles erected on the ground, there is also a ceremony where water lanterns are set on the water, lighting the way for the souls of the drowned. Fearing that the ghosts may be afraid of the world of mortals and will not be able to eat their fill, so cautious towns such as Lukang have patrols that take it in turn to offer sacrificial food each day, after the ghost gate has been opened, so as to keep things safe.

施食

「施食」是普渡中最重要的儀式,信眾供奉豐盛的飯菜以飽眾孤鬼口福。除食物之外,也為其準備經衣(即新衣),讓其在陽間渡過短暫的舒適生活。施給眾鬼的食品,因有法師的科儀,信眾認為食後會帶來好運,因此有搶取貢品的「搶孤」活動,形成普渡過程中最熱鬧的畫面。除了施食之外,也為這些孤魂眾鬼誦經,使其能超渡達於樂土。普渡的尾聲是農曆七月二十九的「關鬼門」,這天傍晚,人們在自家門前準備菜餚,為眾孤鬼「餞別」,廟前的燈篙也要拆除,宣告普渡結束。有時寺廟生怕孤鬼留連不願歸回陰間而危害陽間之人,因此於是日深夜特請鍾馗押孤,以保地方安寧。

The offering of food

The offering of food is the most important rite in the Pudu, and believers make sacrifices of rich dishes to sate the lonely ghosts’ appetites. Apart from food, people also prepare new clothes to allow their passage into the world to be a comfortable one. Because of the discipline rite performed by the priest, believers think that the food for the hordes of ghosts will bring them good luck if they eat it, and so people compete for the food offerings in the “chiang gu” activity, the liveliest scene in the Pudu rite. Apart from the offering of food, people also recite sutras for the wandering souls, so that they can cross over into paradise. The end of the Pudu rite is the “closing of the ghost gate” on the 29th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, and at dusk on that day, people prepare cooked food outside the doors of their homes as a “farewell dinner” for the lonely ghosts, and the lantern poles in front of the temples are dismantled, announcing the end of the Pudu rite. Sometimes, fearing that the lonely ghosts will be unwilling to return to the underworld, and will harm mortals, temples will invite Chung Kuei (a special deity who protects humans from evil spirits) to escort the ghosts, and in this way keep the locality safe and peaceful.

孤魂野鬼在台灣社會裡的特殊意義

七月普渡在台灣漢人社會中,比其在原鄉還來得受重視。十七世紀以來,漢人冒險來台拓墾,毒蛇猛獸、瘟疫、勞累、械鬥、民變,奪走珍貴的人命。「九死一生」的諺語說明瞭其生活競爭的艱辛。遍地無人收埋的屍骨形成先民對鬼魂強烈的畏懼心理。但這些身死異鄉的孤魂野鬼有許多是來自原鄉的兄弟,在宗教與憐憫的驅使下,人民集資收埋曝露的屍骨,形成台灣有應公或萬善祠高密度的現象,台北一個小小的木柵區就有二十六間這樣的祠廟。由於這些客死台灣的孤魂野鬼都是在台灣如兄弟般互相照料的拓墾者,因此七月普渡在台灣稱為「拜好兄弟」,不同於原鄉的「拜人客(即外地人)」。

The special significance of wandering souls in Taiwanese society

The Pudu rite of the seventh month has traditionally been more important in Taiwanese society than it was in the original settlers’ old hometowns back in China. From the seventeenth century, Han people took the dangerous risk of coming to Taiwan to develop the land, and put their lives at the mercy of poisonous snakes, fierce animals, pestilent diseases, backbreaking toil, mob fights and popular uprisings. The old adage “nine deaths, one life” [meaning a situation so dangerous that it would kill nine out ten people] explained the tricky job of fighting to stay alive. Everywhere, the remains of the dead who had no one to bury them created an atmosphere of intense fear about ghosts for the settlers. But these wandering souls of the dead from other places had many brothers from their hometowns, and prompted by religion and pity, people raised funds to bury these exposed remains, and this created the phenomenon in Taiwan of densely-packed graveyards for the unclaimed dead. In the small area of Mucha, Taipei, there are 26 such memorial temples. Because these wandering souls who had died in this foreign land of Taiwan were taken care of like brothers by other settlers here, the Pudu rite in the seventh month was given the name of “honoring our brothers,” rather different from the “honoring strangers” which took place back in China.

就台灣社會發展史觀察,中元普渡的祭典成為十九世紀以後,台灣社會區域人際網路連結重要媒介。這些中元節祭祀的好兄弟,許多是為了保鄉衛民而犧牲的。在祖籍別意識強烈的時代,不同祖籍別的人群各自透過中元節祭典,形成自己的集團,彼此團結,共同面對敵人。台北大龍峒的保安宮是祖籍福建同安縣人中元節的祭祀中心,台北盆地內同安籍人分三組輪流擔任中元祭典主持。艋舺的龍山寺、清水的祖師廟分別是福建三邑(即南安、晉江、惠安三縣)與安溪縣移民的祭典中心。新竹縣新埔鄉枋寮的義民廟是新竹客家祖籍為主的中元節祭祀中心,祭祀在清朝林爽文與戴潮春的反清事件中為鄉而犧牲的鄉民。因其為鄉抵抗反清者,清官方為拉攏賜予「義民爺」。

The connecting medium of interpersonal networks If we look at the history of the development of Taiwanese society, the Chungyuan Pudu ceremony became and important medium for connecting interpersonal relationships in the regions of Taiwan, from the seventeenth century onwards. Many of these “good brothers” of the Chungyuan Festival lost their lives protecting their villages and defending the people there. In an age where consciousness of one’s hometown identity was intense, people with different hometown identities would, through the Chungyuan Festival ceremony, form their own groups, mutually unite, and become a common body against their enemies. The Pao An Temple at Talungtung in Taipei was the center for the Chungyuan Festival rites for descendants of settlers from Tong’an County in Fujian Province, China, and within the Taipei Basin, three groups of Tong’an County descendants would take it in turns to preside over the Chungyuan ceremony. The Lungshan and Chingshui temples in Manka (Wanhua), were the center for ceremonies for the descendents of immigrants from Sanyi (the three Fujian counties of Nan’an, Jinjiang and Hui’an) and Anxi county in Fujian Province. Yimin Temple in Fangliao, in Hsinpu Township, Hsinchu County, is the center of the Chungyuan Festival ceremonies for Hsinchu Hakkas, and at the time of Lin Shuang-wen and Tai Chao-chun’s anti-Qing revolts during the Qing Dynasty, the ceremony was carried out for countryfolk who sacrificed their lives for their hometowns. Qing officials bestowed upon them the name of the “Yimin men” [roughly translatable as “justice men”] on these anti-Qing resisters in order to placate the local people.

台灣七月普渡稱為拜好兄弟實有其特殊的歷史背景。除宗教的意義外,七月普渡成為連結十九世紀台灣中北部社會最重要的媒介。如果人們能以七月拜好兄弟的「熱情」來關懷幫助人間的弱者,則孤魂野鬼或可減少。

Giving the name “honoring brothers” to Taiwan’s seventh month Pudu rite has its own special historical background. Apart from religious significance, the seventh month Pudu rite was the most important medium linking communities together in north and central Taiwan in the nineteenth century. If people could take the enthusiasm from the “honoring brothers” ceremony in the seventh month and apply it to helping their more unfortunate brothers, then they could reduce the number of wandering souls.

Edited by Tina Lee/ translated by Elizabeth Hoile

李美儀編輯/何麗薩翻譯