「影之強敵」 — 日本文化遺緒

「影之強敵」 — 日本文化遺緒

“Shadow foe” — the legacy of Japanese culture in Taiwan

Tsai Mien-tang

2001-11-26

Such traditional Japanese foods as sushi, sashimi, onigiri, etc.

have become customary dietary items in the daily lives of Taiwan’s people.

日本統治台灣期間,正值西方 、 日本 近代化蓬勃發展時期,如同英國促使香港的蛻變,日本亦為台灣帶來近代化的光與影,並留下許多日本文化遺緒。戰後蔣介石政府曾欲禁絕日本文化「遺毒」,但此「遺毒」卻如日語中所謂的「影之強敵」(KAGE NO KYOUTEKI)——存在但看不見的強敵——般,不僅存在,且似已成為台灣文化中的一部分。本週台灣歷史之窗特別邀請淡江大學歷史系教授蔡錦堂執筆,娓娓細數從建築到音樂、從飲食乃至於流行文化--無所不在的日本文物與台灣文化生活的緊密關係。

The Japanese colonial era in Taiwan (1895-1945) coincided with an effervescent surge of modernization in the West and Japan. Just as he British brought about a dramatic metamorphosis in Hong Kong, the Japanese exerted a strong modernizing impact upon Taiwan with bright and dark sides, in addition to which it has left a strong Japanese cultural imprint on its society. In the post-war years, with the return of Taiwan to Chinese rule, the Chiang Kai-shek regime strove to uproot the “residual poison” of Japanese culture from Taiwan, but this “residual poison” has proven to be, as the Japanese might put it, a kage no kyouteki, or “shadow foe” –something not obviously perceptible yet present nonetheless. Indeed, that “poison” not merely continues to exist, but has become a part of Taiwan culture. In this week’s Window on Taiwan, Professor Tsai Ching-tang of the Tamkang University History Department gives us a fascinating, variegated account — ranging from architecture to music, diet to pop culture — of the intimate relationship between ubiquitous “things Japanese” and Taiwan’s cultural life.

現在台灣的社會中,或許在尋常生活中就可以見到下列的現象。如到朋友家,會跟朋友的父母打招呼說「歐吉桑」你好,「歐巴桑」你好;中午吃的食物是「壽司」、「御飯團」或「關東煮」;假日逛街是到「三越」、「SOGO」或「高島屋」;戴的手錶是「SEIKO」、照相機是「NIKON」、開的車子是「TOYOTA」、「NISSAN」;而看的漫畫、電視劇是「家有賤狗」、「名偵探柯南」、「東京愛情故事」等等。台灣社會中充斥著「日本事物」、「日本文化」,這個現象到底是「太陽餘暉」?還是「第二次日據(劇)時期」?

In today’s Taiwan society, we may find the following phenomena in normal, everyday life: When you visit a friend’s home, you might greet the friend’s father and mother with the words “Ojisan, how are your?Obasan, how are you? (polite term for addressing relatively elderly men and women )”; at lunchtime you eat sushi, onigiri, or oden. On days off, you might go shopping at Mitsukoshi, Sogo or Takashiyama department stores; you may be wearing a Seiko watch or carrying a Nikon camera; the car you drive might be a Toyota or Nissan; and the TV programs you watch might include such cartoons and dramatic series as “Our Family Has a Bad Dog,” “Supersleuth Kanan ” or “Tokyo Love Story.” Taiwan society is replete with such “things Japanese” and vestiges of Japanese culture. Are these phenomena indicative of an “afterglow” of an already-set Japanese sun, or of a second “Japanese occupation?”

公私建築裡紀錄過往的帝國殖民夢

造成如此現象的原因有許多,但不能否認地與日本對台統治五十年的歷史因素有所關連。這些日本統治時期的文化遺緒,如果先從看得見的「硬體」方面的建築物觀之,現在的總統府是以前的總督府,行政院是以前的台北市役所(市政府),立法院為台北第三高女校舍,監察院是當時的台北州廳,台北賓館是日治時期的台灣總督官邸,台北中山堂是原來的公會堂,而總統府兩旁的司法大廈與台灣銀行則是日治時期的高等法院與台灣銀行。換句話說,目前台灣政府行政中樞所使用的建築物,大部分是沿用日治時期的遺留物。官廳如此,其他如台北二二八紀念公園、國立台灣博物館、台大醫院舊館,以及各地殘存的公私日式建築物亦如是。

Public and private buildings: reminders of the imperial colonialist dream

Although reasons for this phenomenon are several in number, it is undeniable that it is related in large part to Japan’s 50-year rule over Taiwan. If we first examine the cultural legacy of the Japanese colonial era from the point of view of the “hardware” of buildings, we find that the present-day Presidential Office Building was the former Viceroy’s Office; the Executive Yuan was the former Taipei City Government; the Legislative Yuan was once the Third High School Girl’s Dormitory; the Examination Yuan was the Taipei Syu Administrative Office [“Syu” being one of 3 major adminstrative regions of Taiwan]; the Taipei Guest House [where governmental conferences are held and officials visiting Taipei are temporarily housed] in the period of Japanese rule was the official residence of the Viceroy; Chung Shan Hall was originally the Public Assembly Hall; and the Judicial Office Building and Bank of Taiwan on opposite sides of the Presidential Office Building were, respectively, the Japanese-era High Court and Bank of Taiwan. In other words, the buildings currently being used in the heart of the Taiwan Government administrative district are for the most part buildings in continuous use from the Japanese-era. While this is the case with official office buildings, it is likewise the true of other facilities such as Taipei’s February 28 Memorial Peace Park, the National Taiwan Museum, the older section of the National Taiwan University Hospital and other leftover Japanese-style buildings in public and private use all over Taiwan.

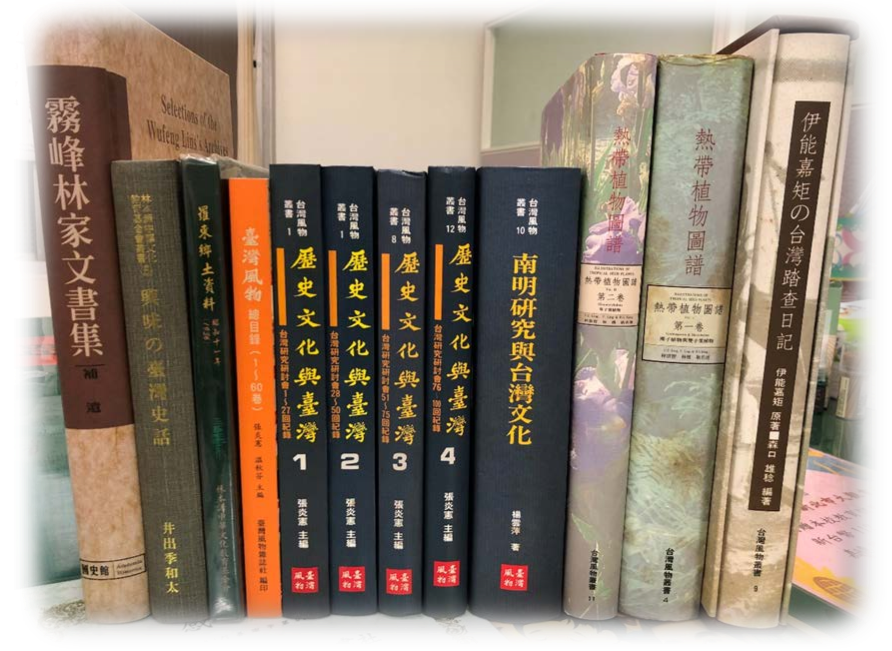

飲食與娛樂生活中的日本文化遺緒

在看不見的「軟體」文化層面,我們亦可觀察到許多日治時期的日本文化遺緒,以飲食而言,壽司、生魚片、御飯團等均已成為台灣人日常生活習慣的食物,而在點吃壽司或生魚片時,許多人是直接使用日語「SUSHI」、『SASHIMI』。基本上SUSHI、SASHIMI等已經變成台灣餐廳或市場中,相當熟悉且「土著化」的名詞。另外,例如常被誤認為台灣傳統食物之一的早餐稀飯佐菜──漬黃蘿蔔,其實亦是自日本傳來的醃製菜蔬TAKUAN。而做料理用的調味品「味素」之名,則是取自日本所發明的化學調味料公司「味之素AJINOMOTO」品牌名稱。至於「便當BENTOH」之名與音,更是無可否認已完全深入台灣民間社會,成為台灣現實生活文化中的一部分。

Traces of Japanese culture in dietary habits and entertainment

Numerous vestiges of Japanese culture from the Japanese colonial era also survive in the form of the less visible “software” of culture. Take food, for instance. Such traditional Japanese foods as sushi (sliced sections of rice rolled together with dried seaweed and other ingredients), sashimi (raw fish slices), onigiri (a type of rice cake wrapped in a hori, or dried seaweed, found in all convenience stores ) , etc. have become customary dietary items in the daily lives of Taiwan’s people. Many people directly use the Japanese pronunciation for these food names rather than Chinese equivalents, such Japanese terms as sushi and sashimi having long been commonplace in restaurants and marketplaces, even to the extent of now having become “nativized” nouns. In addition, a type of rice porridge side dish referred to in Chinese as “pickled yellow turnip” and commonly mistaken for a traditional Taiwanese breakfast food, is in fact takuan (“pickled vegetable”) transmitted from Japan. And the condiment which in Chinese goes by the two-character name 味素 (“flavor essence”) got that name from the famous brand name Ajinomoto (味之素 , with the additional adjectival particle 之) of the Japanese company that first invented this chemically compounded condiment (monosodium glutamate, or MSG). And then there is also the term 便當 (a sort of meal box) which, along with its Japanese pronunciation, bentoh, has even more undeniably entered into common Taiwan society and become a part of practical daily life culture.

日本統治時期,台灣庶民社會的餘暇生活、娛樂方面也產生了很大的變化。受到世界流行的影響,一些新式休閒娛樂漸漸出現,例如撞球、棒球。特別是棒球,日本稱之為「野球」,在日治時期已培養出許多棒球人才,戰後這些人才在台灣1970年代棒球熱時,也貢獻了不少心力;另外,影響所及的結果是台灣的棒球語言,有很多都是日語,例如投手叫PICCHAH,捕手叫KYACCHAH,全壘打是HOMURAN,一壘叫FASUTOH,二壘叫SEKANDOH,三壘是SAHDOH,這些均源自於西文的PITCHER、CATCHER、HOMERUN等的日語化,但亦被台灣棒球界「接收」下來。

During the period of Japanese rule, the leisure-time and entertainment aspects of common Taiwanese society likewise underwent major changes. Under the influence of a world-wide wave of popularization, various novel leisure-time entertainments gradually appeared in Taiwan through Japanese introduction, as for example billiards and baseball. Especially in the sport of baseball — referred to by the Japanese as yakyu (野球 – “field ball”), many talented players were cultivated during the Japanese era, who, in the post-war era, made considerable contributions giving rise to the baseball fever which overwhelmed Taiwan during the 1970s. Moreover, as the result of Japanese influence, baseball jargon used in Taiwan (mainly by the older generation) includes such Japanese terms as picchah (pitcher), kyacchah (catcher), homuran (homerun), fasutoh (first base), sekandoh (second base), and sahdoh (third base). Though variations on the original English terms, it was these Japanified monikers which first took root in the world of Taiwan baseball.

流行樂界裡的東洋風

以流行歌曲來說,在錄音帶、CD等尚未出現之前,聽音樂都使用唱片、收音機,而「唱片」用閩南語發音一般稱為「曲盤」,收音機則叫做「RAJIO」,這也是從日語KYOKUBAN(漢字即寫成曲盤)及英語RADIO的日語發音形成的。

Japanese flavor of pop music in Taiwan

In the realm of pop music, in the days before the advent of tape cassettes and CDs, people were obliged to use vinyl records and radios to listen to music. In Taiwan, records were called Kiok-poan, the Taiwanese pronunciation of the two-character term 曲盤 (“tune platter”) introduced by the Japanese, who themselves who is pronounced it kyokuban. The Taiwan word for “radio” is the Japanified pronouciation rajio.

Japanese-introduced baseball, or yakyu, has become an intimate part of popular Taiwan leisure.

Japanese-introduced baseball, or yakyu, has become an intimate part of popular Taiwan leisure.

台灣的流行歌曲在1920年代至1930年代開始出現,早期這些流行歌曲帶有濃厚的「東洋風」,譬如我們所熟悉的戰前的「望春風」、「雨夜花」、「月夜愁」、「河邊春夢」等,以及戰後的「望你早歸」、「秋風夜雨」、「港都夜雨」等等,其實均受到當時日本流行歌謠創作模式的影響,帶有濃厚的日本味道,只差的是歌詞以閩南語唱出而已。當時日本歌謠界有二大作曲天王──中山晉平與古賀政男,二人在有生之年均譜了三千首以上的曲,而中山晉平於1928年以「無四、七音之五音短音階」樹立日本近代歌謠風,帶有幾分頹廢、哀調。而1930年古賀政男使用吉他等樂器作曲,加上當時著名作詞者西條八十用所謂的「悲劇名詞」作詞,如:風、雨、星、霧、月、秋、網、夢、河、夜、戀、愛、花、愁、船、淚、港、影、心、酒、醉、燈、夕陽、車站、暮色等等,反映出當代民眾生活與心情傾向而大受歡迎。審視台灣之「雨夜花」、「秋風夜雨」等帶有憂愁、頹廢的哀調與歌詞,其實亦受到此類東洋風格的影響。

Taiwanese pop music developed during the 1920s and 1930s, from the very beginning taking on a strong Japanese character. For instance, such well known pre-war Taiwanese songs as “Looking Forward to the Spring Wind,” “Rainy Night Flower,” “Moon-lit Night Sadness,” or “Riverside Spring Dream,” as well as such post-war songs as “Looking Forward to Your Early Return,” “Autumn Wind, Night Rain,” “Harbor Town Night Rain” and many others were in fact all influenced by the model set by Japanese pop songs of the time, carrying a thick Japanese aroma, differing only in that the lyrics were in Hoklo (Taiwanese) rather than Japanese. During those pre-war decades, there were two pop music kings in Japan –Nakayama Shinpei and Koga Masao, each of whom in his lifetime composed more than 3000 tunes. In 1928 Nakayama set the mood for subsequent contemporary Japanese songs with his pentatonic abbreviated scale omitting the 4th and 7th tones, producing a dejected, mournful sound. In 1930, Koga Masao began composing tunes employing the guitar and a variety of other new instruments in combination with lyrics by the then-famous song writer Saijyo Yaso , who typically used a vocabulary of “tragedy-tinged nouns” including such oft-appearing words as wind, rain, stars, mist, moon, autumn, net, dream, river, night, infatuation, love, flowers, remorse, boat, tears, harbor, shadows, heart, wine, drunk, lamp, setting sun, train station, dusk, etc. — resonating with the lives and mood tendencies of the common people of the time, and being greatly appreciated by them. Inspection of such Taiwanese songs, with their dreary, despondent melodies and lyrics, proves them to have been heavily influence by this Japanese tonality.

日本式名字與「台灣化」的日本語文

1940年台灣開始「改姓名」運動,除了部分人改日本姓、日本名外(如李登輝改為巖裡政男、林懷民之父林金生改為牧野雄風、戴炎輝為田井輝雄),也造成日後許多台灣人的名字中帶有「日本式名字」,例如:義雄、文雄、智雄、秀雄、英雄、昭彥、文男、信良、靜枝等。這些名字由於也是以漢字標出,不像一郎、太郎、花子等日式名字容易被察覺,但其實都是帶有日式風味的名字,都受到當時日本文化的影響。一般而言,這些名字較多出現在目前四十至六十歲之間的台灣人身上。

Taiwanization of Japanese words

In 1940 began a name-change movement, [promoted by the Japanese colonial government in order to garner support for its World War II effort]. While a number of Taiwanese changed both their surnames and given names to Japanese names — as, for example, former President Lee Teng-hui, who changed his name to Iwasato Masao ; the father of Li Min-huai [founder and director of the renowned Cloud Gate Dance Troop became Makino Okaze ; or Tai Yen-huei, who took the name Tai Teruo — many more Taiwanese were bestowed with Japanese-style given names at birth, such as 義雄 , 文雄 , 智雄 , 秀雄 , 英雄 , 昭彥 , 文男 , 信良 , or 靜枝 . These and other Japanese-style given names used by the Taiwanese may easily be mistaken for Chinese given names since, besides the fact that both the Japanese and Taiwanese use Chinese characters for their names, the names chosen by the Taiwanese were not so obviously Japanese as, for example, the very common Japanese given names Ichiro , Taro or Hanako . The fact remains, however, that they preserve a Japanese flavor, bearing witness to the imprint left by Japanese culture on life in Taiwan. Generally, such Japanese-sounding names are these days most commonly found among Taiwanese in the 40 – 60 year-old age group.

受到日治時期日本文化影響的事例,最常見到的其實是出現在台灣社會中的「日本語文」,當然這些日本語文已不見得是純粹標準的日本語文,而是經過「土著化」、「台灣化」的日本語文,前述之「歐巴桑」、「歐吉桑」、「便當」、「野球」等等均屬之。這些語詞其實在台灣日常生活中俯拾即是,例如日語中的「新聞」是指報紙,台語稱看報紙為「看新聞」,其實就是日文漢字「新聞」的台語直譯。這種情形在台語文中相當的多,例如「上等」、「郵便」、「注文」、「料理」、「案內」、「萬年筆」、「目藥」、「愛嬌」、「自轉車」、「自動車」、「水道」、「出勤」、「元氣」、「出張」、「會社」、「人氣」、「落第」、「遠足」、「配達」、「見本」、「在庫品」、「勉強」、「看板」、「小包」、「失敬」、「酸素」、「中古」、「運轉」、「住所」、「麥酒」等等。另外如日語的情緒為「氣持KIMOCHI」,台語則將尾音「CHI」省略,直謂「KIMO」。「KIMO」早已成為大家常用的語詞之一。又如日語的「一番ICHIBAN」,也是台灣社會中的慣用語,現在更有人直接以「一級棒」去直譯。

Among the examples of Japanese cultural influence still surviving from the era of Japanese rule, the most commonly occurring are many Japanese-language expressions which have been incorporated into the Hoklo or “Taiwanese” language. Of course that is not to say that all of the Japanese expressions incorporated into Taiwanese are standard Japanese either in orthography or pronunciation. The aforementioned words obasan and ojisan, for example, are rendered in Taiwanese written language as transliterations with orthographic? entirely different from their Japanese counterparts; while the above-mentioned words bentoh and yakyu, while preserving the original Chinese-character orthography, are commonly given Taiwanese pronunciations. In fact, the Taiwanese language used in everyday life is replete with such borrowed expressions. For instance, the Japanese term for “newspaper” is 新聞 [which in Chinese dialects simply means “news”], and this Japanese term has been directly borrowed for use in Hoklo, though with a Hoklo pronunciation of the characters [while, by contrast, in most Chinese dialects, “newspaper” is rendered as 報紙 , or “report paper”]. We may cite many other examples of expressions in Hoklo which are directly borrowed Japanese terms supplanting those used in most Chinese dialects, including, for example, the words for: 上等 first-class, 郵便 mail, 注文 registration, 料理 cuisine, 案內 guide, 萬年筆 fountain pen, 目藥 eye medicine, 愛嬌 charming, 自轉車bicycle, 自動車 automobile, 水道 tap water, 出勤 on duty, 元氣 vitality, 出張 go on a business trip, 會社 company, 人氣 popularity, 落第 fall a test, 遠足 excursion 配達 express 見本 sample, 在庫品 inventory, 勉強 industrious, 看板 billboard, 小包 parcel, 失敬 I’m sorry, 中古 used, 運轉 drive, 住所 residence, 麥酒 beer. Sometimes, Japanese pronunciation is also preserved but with some alteration, as with the Japanese word kimochi, meaning “emotion,” whose final syllable is dropped in Taiwanese to become the widely used word kimo. In other instances, the correct pronunciation is preserved as with the oft-used term ichiban (一番), meaning “number one!” , which some people are given to transliterating using the characters 一級棒 , meaning “first-grade wonderful!”

日治時期的日本文化遺緒已經為台灣社會所吸收而成為台灣社會文化的一部分,如果硬是以「親日」「仇日」的意識型態去簡單化約它,而企求排斥它,或許將會發現此「影之強敵」是難以根除的。

Japanese cultural influences dating from the colonial era have been absorbed and become deeply engrained in the culture of Taiwan society for a long time now. If we look upon this circumstance from the simplistic point of view of a contest between Japanofiles and those who resent the Japanese for their past wrongs, and if the latter side is bent upon rejecting Japanese influences, they may well have to become resigned to the fact that this “shadow foe” is impossible to uproot.

Edited by Tina Lee/ translated by James Decker

李美儀編輯/曹篤明翻譯