台灣歌謠與生活

台灣歌謠與生活

Song and life in Taiwan

楊麗祝/Yang Li-chu

2001-12-03

Combined story-cum-song artist Chen Ta.

Combined story-cum-song artist Chen Ta.

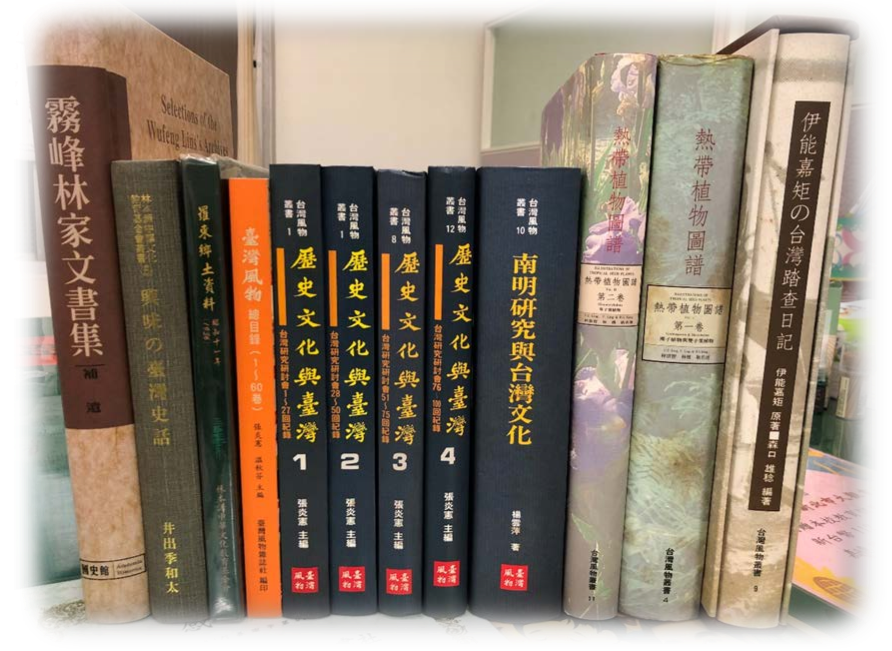

就歷史研究的角度而言,知識階層的詩詞文集與官方的典籍文獻固有參考價值,民間歌謠中大眾生活的圖像勿寧更是鮮活。民謠的內容從歷史故事到社會軼聞無所不包,其中更有男女情挑、敘情相褒。歌句中道出庶民大眾的道德觀與價值觀;也訴說政權更替,人民的痛苦與無奈;對於日常生活的點滴也有生動的呈現。因此,不論是傳統社會中眾多的民謠或工業化、商業化後所產生的城市流行歌曲都紀錄了時代的的變遷與社會的集體意識,亦為大眾生活史的極佳史料。本週台灣歷史之窗特別邀請台北科技大學通識教育中心副教授楊麗祝執筆,引領我們進入台灣歌謠的世界,由歌謠的內涵流衍,感受台灣日常生活裡另一種歷史風貌。

Although, from the standpoint of historical research, the poems and collected essays of a society’s intelligentsia and the recordings of its governmental figures are of course worth attention, the portraits of human life contained in its people’s songs possess a greater freshness and vivacity. Their subject matter includes everything from historical stories to personal anecdotes, not to mention romantic allurements, confessions and adulation. Their lyrics voice the morality and values of the common people; they speak of political transformations and of the people’s sufferings and frustrations; and they are moving expressions of all the little things that make up our lives. Thus, whether it be well-known, more traditional folk songs or the contemporary urban-flavored popular songs in the era of industrialization and commercialization of music / human activities, the songs people sing constitute records of the evolutionary changes and collective consciousness of a people during different eras. As such, they are invaluable historical source materials for understanding the lives of a people. This week’s Window on Taiwan has invited Associate Professor Yang Li-Chu of the National Taipei University of Technology, Center for General Education to lead us into the world of Taiwan song and, through an examination of songs’ contents and evolutionary courses of development, to get a feeling for another side of daily life in Taiwan through the ages.

一般而言,我們可以將「歌謠」分為自然歌謠與創作歌謠,前者又稱為民歌或民謠,其特點是大多不知作者為何人,以口頭方式流傳,在流傳過程中其詞曲會因人時地的不同而有所改變,所以有人說民謠的作者就是民眾自己,它反映的是一個民族特有的情感,是民族性的表現;而後者指個人的創作,作者追求作品的市場性、藝術性或永恆性而創作,如流行歌曲、藝術歌曲等屬之。

Broadly speaking, we may distinguish “songs” as being either “natural” or consciously composed. The former class of songs, also known as “folk songs,” are characterized in that, for the most part, no one knows their original creators, and they are transmitted from person to person, the lyrics changing with the people who sing them and the times as they are passed on. For this reason, some people say that the creators of folk songs are the people as a whole, reflecting the sentiments particular to a people and constituting an expression of their group identity. The latter class of popular songs comprises those authored by individuals, whose creations may be motivated by commercial, artistic and/or eternal values. Pop songs and artistic songs are of this latter class.

其實如此劃分也有其缺失,一首古老的民謠在當時必是流行的,初期也是個人的創作,只是在流傳過程中作品不斷的被修正,加之年代日久,作者漸不可考。而一首歌曲是藝術或流行歌曲本不易區隔,雖同屬個人的創作,但只要被大眾認同喜愛,自然會流傳下來,眾人可任意的加以解讀,也可從中看到大眾的生活與與情緒。

Actually, this distinction is somewhat flawed inasmuch as an ancient folk song was originally a pop song of its time, composed by an individual, and it is only due to the endless modifications of it as it was transmitted and the changes it underwent through successive generations that its authorship has come to be uncertain. Moreover, it is not easy to draw a sharp distinction between an “artistic” and a “popular” song. Although both are the creations of individual composers, as long as they are beloved and identified with by the public, they will naturally be passed down, the people infusing them with their own meanings, enabling us thereby to see in them the lives and sentiments of an entire people.

Taiya tribespeople singing as they grind grain.

Taiya tribespeople singing as they grind grain.

原住民音樂的流行

在漢人大量移入之前,台灣本係原住民社會,昔日不論是居住於西部沿海平原的平埔各族或生活在中部山區及東部的山地原住民族群,歌舞音樂與其日常生活是習習相關的,從工作居家生活到祭典禮儀皆有歌舞的呈現,故歌謠不僅是娛樂、抒情而已,更有宗教、社會等功能。由以下歌謠的名稱,如耕農歌、狩獵歌、捕魚歌、祈禱小米豐收歌、戰歌、驅魔歌等,可略窺原住民社會中的不同層面,至於情歌在部份原住民社會中更有男女婚訂的功能。由於台灣原住民只有語言而無文字,因此歌謠除上述功能外,更是傳承歷史記憶的工具,像祖靈歌、傳說歌等均屬之。

Evolution of Aboriginal music

Prior to the large-scale influx of ethnic Han Chinese people into Taiwan, Taiwan was originally constituted of Aboriginal societies. In times past, whether it was the various Pingpu tribes in Western Taiwan, or other tribes in the central mountain regions or in eastern Taiwan, song and dance were inseparable parts of daily life. Singing and dancing were found in all aspects of life, from individual households to group rituals, and songs were vehicles not merely for entertainment or expression of individual emotion, but had religious and social functions. From the themes of their songs — such as farming songs, hunting songs, fishing songs, prayerful songs for a bountiful millet harvest, warring songs, songs for driving away evil spirits, etc. — we can get some insights into different aspects of Aborigine life, and in some Aborigine societies love songs played a role in courtship. Because Aborigine languages were only oral and not written, besides serving the aforementioned purposes, their songs functioned as tools for preserving historical memories, such songs including, for example, ancestor-spirit songs and legend songs.

不過隨著漢人移民的進入台灣,西部地區快速的「水田化」,以漁獵、旱耕為主要生活形態的原住民部落,隨著生活空間的日漸消逝,平埔族被稱為「消失的族群」,而山地原住民社會面對強勢的外來文化,也逐漸改變其風貌,其歌謠音樂自然隨之蛻變。十九世紀西洋傳教士所帶來的教會音樂,使今日原住音樂中多了聖樂歌詠的部份。半世紀的日本殖民統治使日本文化深入原住民社會,其影響自不待言,由有些阿美族民歌中漢族小調及日本小調風格可見一般。

With the coming of Han immigration into Taiwan, however, and with the “paddification” of western Taiwan [i.e. transformation of western regions into flooded rice paddies] and the gradual shrinkage of space left for the fishing, hunting and dry-land farming lifestyles of Aborigine tribespeople, the Pingpu came to be referred to as a “lost race,” and under the pressure of a dominant alien culture, Aborigine societies gradually changed in demeanor, their songs naturally undergoing a parallel metamorphosis. As the consequence of the coming of Christian missionaries in the 19th century, religious hymns have now become incorporated as a part of Aborigines’ music. A half century of Japanese colonial rule injected a strong dose of Japanese culture into Aborigine societies, having an undeniably deep influence upon them. These influences are evident in the Japanese- and Han-flavored melodies used, for example, in the folk songs of the Ahmei tribespeople.

在西洋流行音樂風行全世界的今日,台灣熱門樂壇出現的原住民的歌手替樂壇增一股新聲,也讓不少原住民傳統民歌得以重新包裝呈現在唱片市場。原住民已接受音樂是休閒娛樂或消遣性的行為,而都市化後遷居城市的原住民也透過歌曲表達了他們在現實生活中的掙扎與無奈,借此凝聚遠離鄉土原住民的心,「流浪到台北」、「我們都是一家人」等歌曲的流行,可為映證。

In today’s world where Western pop music has become ubiquitous, Aboriginal singers who have emerged in the Taiwan pop music scene have given it a new voice, enabling quite a few traditional Aboriginal folk songs to enter into the music record market in repackaged form. For Aborigines, who have now come to accept music as a form of entertainment or leisure activity, and who, in the wake of urbanization have moved into the cities, song has become a medium for expressing the struggles and frustrations in their practical lives and a means for crystallizing the sentiment of a people separated from their homelands, as reflected, for example, in the popularity of such songs as “Wandering to Taipei” or “We are All One Family.”

台灣漢人歌謠的內涵

除卻原住民外,占台灣人口大宗的漢人是十七世紀後隨移民潮一波波進入台灣的,他們不僅帶進了原鄉的生活方式,也將音樂歌舞活動傳入。不論來自福建或廣東,原鄉的民謠經過台灣風土的洗禮後,也形成具本土特色的民謠。數量甚豐的福佬系及客家系民謠是先民重要的精神文化食糧,也見證了台灣歷史的發展。

Han folk songs content

Besides Taiwan’s Aboriginal peoples, the ethnic Han majority, who have immigrated to Taiwan in wave upon wave from the 17th century onward, have not only brought with them the lifestyles of their homelands but their song and dance traditions as well. Whether originating in Fukien Province or Kwuantung Province, after undergoing the baptismal process of Taiwan nativization, they too became folk songs reflecting local culture. The massive compendium of Fukienese and Cantonese folk songs not only served not only as the spiritual fount of the early Han immigrants to Taiwan but stands as testimony to Taiwan’s historical development.

依歌詞的內容來看,台灣漢人民謠大致可分為以下幾類:一、家庭倫理類,如「病子歌」、「做人的媳婦」、「滿月歌」等;二、工作類,如「採茶歌」、「牛犁歌」、「乞食調」等:三、祭祀類,如「牽亡歌」、「道士調」等;四、敘述類,如「勸世歌」、「時令歌」、「鄭成功開台灣」等;五、諧趣類,如「嫁尪歌」、「飲酒歌」、「猜拳歌」等;六、愛情類,無論古今中外愛情可說是歌謠中永恆的主題,不論是福佬系或客家系民謠都不例外,情歌所佔的比率甚高,像客家山歌就有不少男女相褒談情說愛的歌句;七、童謠類,童謠是兒童生活中所哼唱的歌曲,其內容相當廣泛,在學校教育不普及的前近代社會,童謠不僅是兒童們的娛樂,也具啟蒙的功能。

Based upon lyrics, Han folk songs can be broadly classified as belonging to the following several types: (1) FAMILY VALUE SONGS – as for example, “sickness songs” [sung by expectant women to their unborn babies and to themselves in hopes that their own illnesses would not affect their babies] “Becoming a Daughter-in-Law” or “full-month songs” [celebratory songs sung at the time when a new-born baby reaches one month of age, in order to bring good fortune for the child’s future development]; (2) WORK SONGS – as for example, tea leaf-picking songs, water buffalo-plowing songs or food-begging songs; (3) RELIGIOUS SACRIFICIAL SONGS – as for example, spirit-guide songs [for guiding the spirits of newly deceased in their after-lives] or Taoist liturgical songs; (4) NARRATIVE SONGS – such as exhortatory songs, season-related songs or “Cheng Cheng-kung Opens Up Taiwan” [Cheng Chen-kung was a military-political figure who came to Taiwan from China in an effort to keep the Ming Dynasty alive in the early years of the Ch’ing Dynasty, established by the Manchu people of present-day northeastern China] ; (5) HUMOROUS SONGS – such as betrothal songs, drinking songs or hand-gesture game songs [songs sung in accompaniment to games involving rhythmically changing hand gestures (such as paper-stone-scissors), often sung in group drinking, the loser having to “bottoms-up”] ; (6) LOVE SONGS – an eternal theme in songs ancient and modern, constituting a large proportion of either Fukienese or Hakka ethnic folk songs — Hakka “mountain songs,” for example, including many with romantic lyrics; and (7) CHILDREN’S SONGS – sung by children in their daily lives and including many themes, which, in the days before modern-day universal education, served not only as a form of entertainment but a vehicle for inculcating early lessons in life.

Modern singer Lo Ta-yiu, known for the social-protest flavor of his early songs.

Modern singer Lo Ta-yiu, known for the social-protest flavor of his early songs.

流行歌曲市場的興起

二十世紀初期殖民化、近代化的腳步,使台灣社會的變遷加速,工業化、商業化的結果使都市的人口驟增,於是以都會居民為消費對象的城市小調興起。如果說民間歌謠是古老的鄉土樂音,那流行歌曲就是現代城市中的歌唱。一九二○年代前後台北市有唱片公司出現,三○年代台語(台灣社會一般稱閩南語為台語)流行歌風行一時,與歌仔戲同為民間的主要消遣娛樂。這些由唱片公司請專人作詞作曲,符合大眾流行品味的歌曲,其中不乏詞曲俱佳作品,如現今大眾仍朗朗上口的「望春風」、「雨夜花」「月夜愁」等。為數眾多幽怨哀愁的流行歌曲是鬱積年代人們心情的反映,殖民統治者雖高唱進步的神話,卻抹不去人們心頭的傷痛,流行歌樂成為殖民統治下苦悶心靈的最佳代言。

Emergence of the pop music market

20th century [Japanese] colonialization and modernization occasioned an acceleration of social change in Taiwan, and, as the result of the rapid growth of urban populations stimulated by industrialization and economic development, there arose urban life-oriented tunes aimed at city-dwelling consumers. If folk songs can be characterized as ancient, broadly “native” music, then pop songs are the songs of modern-day urbanites. Just prior to, through and beyond the 1920s, record companies sprouted up in Taiwan, while in the 1930s “Taiwanese” (i.e. Hoklo, or southern Fukien dialect) pop songs came into vogue, with ko-tsai-hsi [Taiwanese-language “song plays” similar to Western musicals] becoming a major form of entertainment. These record company-commissioned songs in tune with the popular consciousness included not a few outstanding examples such as “Looking Forward to the Spring Wind,” “Rainy Night Flowers” or “Moon-lit Night Sadness,” which everyone even to this day loves to join in singing. The predominantly mournful pop songs of the period are a reflection of a cumulative popular malaise which grew over the decades. Despite the Japanese colonialists’ ballyhooing of the myth of “progress,” this could not diminish the feeling of hurt in the people’s hearts, popular music becoming the most obvious mirror of that ever-suffering spirit of a people under colonial rule.

戰後的台灣,雖重回祖國的懷抱,但百業蕭條,社會失序,二二八事件、白色恐怖接踵而來 come in quick succession/follow on the heels of,在政治操控嚴密,經濟逐步起飛的年代,流行歌樂雖不免被禁制改編,官方也以意識形態掛帥,刻意提倡國(華)語歌曲、愛國歌曲、淨化歌曲,但在不同的時期流行歌曲仍是大眾生活的最佳調劑,不論用的是國語抑或台語,其中有個人情感也有家國之思,歌詞內中國大陸固然是不少人心中的夢土,有濃厚鄉土之愛的歌曲也不匱乏,而更多的是記錄台灣社會形形色色的歌句。

Despite the return of Taiwan into the bosom of China after World War II, it was followed by successive economic depression, social unrest, the February 28 Incident and the White Terror; and due to tight political control during the years when Taiwan’s economy took flight, various prohibitions were unavoidable and sensitive lyrics had to be rewritten, as officialdom, driven by its ideological mindset [of reconquering China], made a concerted effort to promote “national language” (Mandarin) songs and patriotic songs while banning public performance of certain songs. Nevertheless, throughout various post-war periods, popular music remained the best vehicle for keeping the emotions in balance. Whether the language of song was Mandarin or Taiwanese, it conveyed personal feelings as well as thoughts on family and country; and although, to be sure, the lyrics of many a song projected mainland China as the dreamland of many, there were also not a few songs which retained a strong feeling of love for the native soil of Taiwan, and even more numerous were songs with lyrics which recorded the many sundry aspects of Taiwan society.

七○年代以後現代民歌運動興起,爾後清新的校園歌曲,成為流行音樂的主流,八○年代後隨著政治的鬆綁,流行歌曲的內容更趨多元,更能反映社會的諸多現象。不過在商業勢力的的併吞下,唱片業日益規模化,樂界開始重視歌手的塑造,偶像歌手成為年青人學習的對象,流行音樂中,「人」比「歌」的本身更形重要,市場上偶像歌手的汰換令人目不暇給,而暢銷歌曲更是稍縱即逝。民謠的年代早已遠去,正如同傳統的生活方式一去不復返是一樣的,當然懷舊仍然可以成為商品,不論是深具古早味的民謠或是雋永的老歌,仍為消費商品的歌曲與時代轉換的見證者。

The 1970s saw the upsurge of modern-day folk songs, after which refreshingly new “campus songs” [composed by college students in government-sponsored competitions] came into the mainstream of popular music. Following upon political liberalization in the 1980s, the content of pop songs became more diversified and thus more able to reflect all manner of social phenomena. However, under the overwhelming influence of commercialization plus homogenization of the record industry, the music scene came to place increasing attention on molding singers’ public images. Singing idols became the models for youths’ imitation, and, in popular music, the person of the singer became more important that the song itself. The replacement of one singing star by another in the music market has proceeded in dizzying succession, and best-selling songs no sooner appear than fade away. The age of folk songs has now long passed and, as with the passing of traditional lifestyles, once gone will not return. Of course, nostalgia for earlier times can nevertheless still be transformed into commercial products, and in that role, whether they be folk songs with an ancient flavor or undying old favorites, they serve not only as consumer items but as witnesses to the changes of the times.

Edited by Hsu, Shiou-Iuan/ translated by Elizabeth Hoile

(李美儀編輯/曹篤明翻譯)